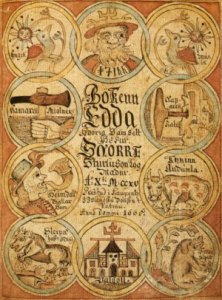

Mythology is key to understanding Beowulf. As I told my colleague’s students in a recent guest lecture, MYTHIC STRUCTURES typical such those as articulated in, for example, Snorri Sturluson’s thirteenth-century Prose Edda, function as follows.

Gods create Middle-Earth, building a wall to push away monsters, giants and frost ogres to the borders of the world. To celebrate and contain a space of peace they build a palace.

Thjazi and Loki. Beginning of the myth of the abduction of Idun, reported by Skáldskaparmál. Manuscript NKS 1867 4to (Iceland, 1760), Copenhagen, Royal Library

Eventually, chaos monsters transgress the borders, invade the space of peace (the palace), overcome the gods, and bring about the end of the world.

STRUCTURES IN SAGA

On the level of saga, this structure is played out within the scope of a nation. You can read about Frothi here. He rules Denmark at the time of Emperor Augustus when peace reigns over the whole world. “No man injured another, even although he was confronted with the slayer of his father or brother, free or in bonds. Neither were there any thieves or robbers, so that a gold ring lay untouched for a long time on the Heath of Julling.” Frothi’s peace and prosperity is overrun by giant women who grind out an army with a mill: “With that the Peace of Frothi came to an end.”[1]

Fenja and Menja (giant women disguised as slave girls) at the mill. Illustration by Carl Larsson and Gunnar Forssell.

STRUCTURES IN BEOWULF

The mythic structure describe above is present in Beowulf on the level of the nation. Gods are displaced from the cosmic level to the human level and are replaced by a Christian God.

The BBC reported in 2012 about a provocative and poignant discovery: the skull of an Anglo-Saxon girl was found with a jeweled symbol of Christianity

Scyld Scefing carves out a peaceful land. The border area is where monsters such as Grendel and his mother lurk. A hall is built by Hrothgar to celebrate the exclusion of such bad characters. But the joy is doomed to imminent sorrow.

The Anglo-Saxon feasting hall unearthed in Lyminge, Kent Photo: UNIVERSITY OF READING. You can read about this discovery here.

The hall is invaded at night. Ultimately the nation is destroyed and dissolved. Beowulf rules for fifty years successfully (2732b-39a), but after he is killed, his kingdom is doomed (3014-27). The Lay of the Last Survivor expresses this sense of impending doom for once glorious kingdoms poignantly and succinctly2262b-66). All cultural artifacts will eventually tarnish and decay (lines 2255-6).

The walls will be destroyed. The gold-adorned walls will be covered in gore and blood.

[1] Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda, Jean I. Young, trans. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954): 118.

Follow me on Twitter: @medievalwomen

It’s psychological too. We sense our mortality and even more deeply the shakiness of our ego-construct — it’s more shape-shifting than solid if we really examine it — and we feel a queasiness about this insecurity. So we project our fears of this inherent impermanence onto monstrous forces “out there” that seem to threaten our temporarily constructed and ever vulnerable sense of safety. And as long as we rely completely on such a separate self for our sense of identity, we are doomed, and deep down we know it. Hence the mythology predicts chaos will win in the end. However, to me, from a basically Buddhist perspective, the deep quest of being alive is to find out if there is something that isn’t at the complete mercy of such conditions — something that never dies, and not in the form of a wishful faith that we can live on as an eternal separate soul (as if our personal ego could just sprout wings and become an angel if we behave just right.) So there’s a deep psychological truth to the apocalyptic mythology you describe, but it doesn’t have to be the last word about who we really are or what our ultimate fate can be. (Loved your book, by the way.)

LikeLike

I totally agree that we feel ourselves to be insecure (we could die at any moment), so we project this fear onto others. Often onto vulnerable “others” who seem different than us, who embody the threat of our own vulnerable mortality. I think that thing that is the “something that isn’t at the complete mercy of such conditions–something that never dies” in the Anglo-Saxon world is honor. Acting ethically and honorably according to the codes of conduct the culture endorses is the one way to preserve your name. If you boldly stand firm even when bad-ass Vikings are about to hack you down, you win. And thanks for loving my book!! 🙂

LikeLike